Stars over Tyrrell: The night sky of the Boorong

Words, voices and images: Connecting to cultures around the world

Words, voices and images: Connecting to cultures around the world

We publish this web version of Stars over Tyrrell: The night sky legacy of the Boorong to honour John for his detailed and long term investigations of the Boorong night sky and for his deep understanding of why the Boorong must be remembered in the stars and night sky that so shaped the lives of Victoria’s Aboriginal people.

We would like to thank the astronomer and photographer, Alex Cherney, for his superb photos and time lapse movies of the Boorong night sky.

Thank you to Rob McLean for his photo of Western Grey Kangaroos.

We are grateful for the interest and encouragement shown by Doug Nicholls and Alan Burns, Bruce Baxterat Swan Hill primary school, Rodney Carter the chairperson of Swan Hill and District Aboriginal Cooperative, Boondy Walsh the Koorie Programs Convenor and students in Koorie Art and Design at Swan Hill TAFE.

We are grateful also to citizens of Sea Lake who have shown an interest in this research and subsequent projects, especially to Kate Atkin, Rob Frankland, John Horan, Wendy Hersey and Keva Lloyd.

A very special thank you to Kirsty Morieson for her assistance and friendship.

William Stanbridge 1857 On the astronomy and mythology of the Aborigines of Victoria, Proceedings of the Philosophical Institute, Melbourne

David Mowarjali and Jutta Malnic Yorro Yorro, Magabala Books 1993

Luise Hercus 1969 The language of Victoria: a late survey ANU

Luise Hercus 1992 Wemba Wemba Dictionary AIATSIS

R H Mathews 1904 Ethnological notes on the Aboriginal Tribes of New South Wales and Victoria, Part one, Royal Society of New South Wales

Ian Ridpath and Wil Tirion 1988 Collins Guide to Stars and Planets Collins

John Morieson 1996 The night sky of the Boorong, MA thesis, University of Melbourne

Mallee Fowl image - Russotwins/ Alamy stock photo

One hundred and fifty five years ago, a Boorong family at Lake Tyrrell told William Stanbridge something of their stories relating to the night sky.

One hundred and fifty five years ago, a Boorong family at Lake Tyrrell told William Stanbridge something of their stories relating to the night sky. Some forty stars, constellations and other celestial phenomena were named and located.

William Stanbridge wrote them down and related this information in an address to the Philosophical Institute in Melbourne in 1857. In his paper he wrote down the Aboriginal term and its European equivalent. What I have done is to look for these creatures and people in the night sky, attempt to satisfactorily identify them and to draw them in the way the Boorong people may have seen them.

I believe the way they saw them relates directly to the way they lived in the Mallee environment in north-west Victoria. Becoming familiar with this country then helps me find out what is in the sky. The basis for understanding the connection between earth and sky is derived from an expression by David Mowaljarli, who said that:

“Everything under creation is represented in the soil and the stars”.

To unravel the names of the sky-beings I focussed on the ground, but also found clues in the stars, in their colours and where they appeared in relation to each other.

A special feature of north-west Victoria is the sky, blue and often cloudless during the day, and a spectacular star filled vista at night. Stanbridge said that:

“The Boorong pride themselves upon knowing more of Astronomy than any other tribe”.

The name “Tyrrell” (direl) is the Boorong word for sky. On an occasion when there is water in the lake, on a cloudless night when the water is still, every star in the sky can be seen reflected. Out in the lake it is easy to form the impression that one is in space, with the stars all around, above and below. Direl had both meanings, sky and space.

Creating a meaningful understanding of these sky-earth connections and thus of the recent past is the main purpose of this monograph.

One hundred and fifty five years ago, a Boorong family at Lake Tyrrell told William Stanbridge something of their stories relating to the night sky. Some forty stars, constellations and other celestial phenomena were named and located.

William Stanbridge wrote them down and related this information in an address to the Philosophical Institute in Melbourne in 1857. In his paper he wrote down the Aboriginal term and its European equivalent. What I have done is to look for these creatures and people in the night sky, attempt to satisfactorily identify them and to draw them in the way the Boorong people may have seen them.

I believe the way they saw them relates directly to the way they lived in the Mallee environment in north-west Victoria. Becoming familiar with this country then helps me find out what is in the sky. The basis for understanding the connection between earth and sky is derived from an expression by David Mowaljarli, who said that:

“Everything under creation is represented in the soil and the stars”.

To unravel the names of the sky-beings I focussed on the ground, but also found clues in the stars, in their colours and where they appeared in relation to each other.

A special feature of north-west Victoria is the sky, blue and often cloudless during the day, and a spectacular star filled vista at night. Stanbridge said that:

“The Boorong pride themselves upon knowing more of Astronomy than any other tribe”.

The name “Tyrrell” (direl) is the Boorong word for sky. On an occasion when there is water in the lake, on a cloudless night when the water is still, every star in the sky can be seen reflected. Out in the lake it is easy to form the impression that one is in space, with the stars all around, above and below. Direl had both meanings, sky and space.

Creating a meaningful understanding of these sky-earth connections and thus of the recent past is the main purpose of this monograph.

"The Boorong people claim and inhabit the Mallee country in the neighbourhood of Lake Tyrill, and pride themselves of knowing more of astronomy than the other clans".

So wrote William Stanbridge in 1857 referring to his experiences a decade earlier.

They were one of about twenty clans who shared the Wergaia language and whose only known legacy is this information about the night sky, the parish name Boorongie, 30 kilometres north-west of Lake Tyrrell.

It is likely that they lived in the region for a long time. A carbon date taken from charcoal found at the north end of the lake is dated at 23,000 years. The charcoal was found in association with burnt clay, Emu eggshell and a chert artefact, thus suggesting human occupation.

Their astronomical prowess appears to have been widely known and maybe the reason for their name, which means “darkness” or “night” in the local language.

Wergaia language extended as far north as Ouyen, northwest to Murrayville, southwest to Serviceton and east through Dimboola and Warracknabeal to Charlton on the Avoca River.

As the land was taken over by the invaders so the Wergaia speakers did what they could to survive and for a time sought refuge at Ebenezer Mission, north of Dimboola and at Lake Boga, near Swan Hill. Their descendants are represented today by the Goolum Goolum Aboriginal Cooperative at Horsham.

That this fragment of the night sky lore of the Boorong exists at all is due to William Stanbridge.

Stanbridge was twenty years of age when he arrived in Port Phillip from Warwickshire in November 1841. The colony was six years old. He teamed up with Lauchlan Mackinnon and moved on to the Broken River in North East Victoria to learn about managing outback sheep stations there and in other remote parts like Swan Hill, Mount Gambier and Lake Tyrrell.

He purchased pastoral leases at Lake Tyrrell and Daylesford in the late 1840s and early 1850s and at Lake Boga in the early 1860s, intending to move his sheep between north-west and central Victoria, depending on the climate and sheering needs.

Stanbridge grew rich from gold found on his Daylesford holdings during the 1850s. In Daylesford he got to know Edward Stone Parker, who as an assistant protector of Aborigines set up a station at nearby Mount Franklin to provide sanctuary for the remnants of families and clans. Stanbridge wrote:

“The Aborigines in the neighbourhood of Mount Franklin have names and mythological associations for a few of the stars, which names and associations are the same in use with the Boorong’s….”

William Stanbridge seems to have been a decent, generous, sensitive man who used his position in society more for the public good than for personal aggrandisement. We can deduce from his writings that his attitudes towards Aboriginal people were relatively positive and somewhat respectful, as he hoped others would feel.

“The astonishment that I felt, as I sat by a little campfire, with a few boughs for shelter, on a large plain, listening for the first time to Aboriginals, speaking of Yurree Wanjel, Larnan-kurrk, Kulkan-bulla, as they pointed to these beautiful stars”.

We are grateful for the fact that William Stanbridge bothered to listen, to remember and to have this fragment placed on the record when, as a member of the Philosophical Institute in Melbourne, he gave an address on this topic in September 1857. It was printed in the Institute’s proceedings for that year.

Over twenty locality place names in north-west Victoria coincide with Boorong constellation names.

They include

David Mowaljarli has provided the inspiration and the insight from the traditional Aboriginal perspective in this research.

A Ngarinyin elder from the Kimberley, he has been a member of the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies and of the Aboriginal Arts Board of the Australian Council.

His book Yorro Yorro, the culmination of a six year project with Jutta Malnic, a Sydney photographer, is part of a self-imposed commitment by David Mowaljarli to document all he knew for the sake of his grandchildren and future generations.

David’s two eldest sons died in custody. David died not long after his second son had died. He was custodian of several Wandjina sites in the Western Kimberley. I wanted to ask him about the Wandjina like figure in the central star in the belt of Orion (see Kulkunbulla) because everything for him existed twice, once on the ground and the other in the sky.

“ Everything has two witnesses, one on earth and one in the sky. This tells you where you came from and where you belong”.

In other words, the knowledge written in the sky is the story of the creation and of the law. This principle allows us to view the components of the Boorong night sky in a traditional context and thus to deduce something of the seasonal and the cultural lives of the Boorong clan.

Stanbridge mentioned four seasons of the Boorong and gives the European equivalents. He cites ‘Weeit’ (Autumn) as the first season of the year, and “Cotchi’ (Summer) as the fourth season.

Since Emus begin to lay their eggs in the autumn and because the Emu egg taken up into the sky by Pupperimbul becomes the sun, and because the sun is the giver of life, it stands to the reason that autumn should be the first season.

And since summer is the season of the great heat, when water, the other essential in life becomes scarce, and grasses die off, it is sensible to regard this as the final season of the year.

It is also apparent that the Boorong noted the repetition of the constellations, year after year, and subsequently related particular stars and constellations to events on the ground, for example:

“Marpeankurrk (Arcturus) - the discoverer of Bittur, and the teacher of the Aborigines where and when to find it - duringt he months of August and September”.

“Neilloan (Lyra) - when the Loan eggs are coming into season on earth, they are going out of season with her. When she sits with the sun, the Loan eggs are in season”.

“Purra (Kangaroo) (Capella) - who is pursued and killed -at the commencement of the great heat” and when the cooking fire smoke has gone, “Weeit (Autumn) begins”.

It seems that an examination that one or more of the creatures are prominent in the sky each month and an ecological Zodiac can therefore be devised. However all of these items constitute animal protein. That there are no vegetable items in the Boorong pantheon may be because of Stanbridge’s informants were men. Men are the hunters; women are the gatherers.

In other regions, seeds, plants and tubers find expression in the story, star and symbol.

The ancestral beings instituted a way of life that they introduced to human beings and because they are eternal, so are the patterns that they have set. In which case it might be of interest to examine some of the species chosen to represent the ancestral beings in the Boorong night sky, for example the Owlet Nightjar, the Malleefowl, Eagle and Crow, and the Brolga from a perspective of family.

Yerredetkurrk: It is easy to see that the qualities of the female Owlet Nightjar as being both feminine and mothering. Skill at food gathering, determined protection of the young, attractive appearance and maintenance of a clean house are behavioural characteristics that might give this bird a special place in the eyes of women.It is not surprising to read therefore that the Owlet Nightjar was a totem for all women in south-eastern Australia.

Neilloan: The Malleefowl pair for life and the male and female have strongly defined gender roles, the focus of their activity is the production of the next generation; they cooperate well together while each has their special part to play in family life. A parent and child observing the Malleefowl could note all kinds of details about the female role, the male role, the teamwork, the specialisation, the mutual defence of territory, the daily search for food and the patience and tenacity required during the whole breeding period. Observation of Neilloan in the sky would reinforce what is observed on the ground.

Warepil the Wedge-tailed Eagle, is supported in the Boorong sky by his wife Cullowgulloric Warepil. Warepil’s brother War the Crow is also there with his wife Cullowgulloric War. Both these husbands and wives mate for life, occupy a defined territory, rear only one child (usually) at a time. Husband and wife sharing in the nurturing, feeding and protection of the child until it is grown up. The Eagle’s courtship display is wonderful to see and the territorial duties of the Crow are well known.

Kourtchin: The third family pair are the male and the female Brolga. They also mate for life, raise their children and are admired for their dance.

It is not surprising that these particular species find themselves in the celestial array of the Boorong given and that the specific behavioural elements mentioned would be well known to them, considering the thousand plus generations that lived successively around Lake Tyrell.

People in oral cultures do not ‘study’ to acquire wisdom. They learn by apprenticeship, discipleship, by listening, by repeating what is heard, by remembering and by contemplation.

Oral cultures create their knowledge through graphic description of their life world. Strong characters, physical violence, exciting adventures and a well-defined morality form the basis of easily remembered stories. Within the stories are seasonal factors, meteorological information, hunting advice and survival techniques, along with depiction of human behaviour.

In Aboriginal society, which is so closely attuned to nature, there appears to be no distinction between the creatures and the people. In fact people identify with particular creatures or things to distinguish themselves, their family lines and their consequent relationships with others.

This makes it easier to know whom they can marry and whom they can’t, which is an absolutely vital consequence of living in small populations where marrying too close a relative can produce mental or physical defects in the offspring.

Emphasis in traditional learning is on silent observation rather than verbal instruction, on imitation rather than problem solving, on rote learning rather than question and answer, on role-play rather than passive participation and real life activities rather than repetitive exercises.

Which human senses are used in learning? In contemporary mainstream secondary schooling the emphasis is almost entirely on the visual. For young people in Aboriginal society several senses are relied on. To act out a dreaming story, for instance, the bodies will be painted (tactile and visual senses), the story will be danced (kinaesthetic sense) and sung (auditory sense). All the senses are drawn upon. Each reinforces the other.

This is why it was not necessary to have a written culture to ensure the survival of knowledge and successfully living across the centuries.

As far as the stars are concerned, the sky is the metaphor for life on the ground. As children are introduced to the ancestral beings and stories in the night sky, so they are prepared for life on earth.

There are two strong threads running through the Boorong use of the night sky, one ecological, the other moral. The behaviour of the ancestral creator beings can be judged as positive and therefore good, or negative or therefore bad. Tchingal eats people. He is bad. He is killed. The brothers Berm kill Tchingal. This is good because the people are released from their fear and oppression.

Totyarguil throws a boomerang at his mother-in-law. This is bad. His mother-in-law causes him to finish up in a pond ripped to pieces by a monster. His uncle rescues him and puts him back together. This is good. This is the behaviour to be expected of the mother’s brother who has a special relationship with his sister’s son.

Mityan the moon wants to seduce one of Unurgunite’s wives. This is bad. Unurgunite beats him up and sends him packing. This is good. Mityan is forced to wander the heavens ever since.

The physical movement of Totyarguil into the sky, when he reaches his highest point and when he leaves the sky, are in opposition to the movement of his mother Yerredetkurrk, who is most visible when Totyarguil is not so far. This movement of opposites reflects the way in which mother-in-law and son-in-law are supposed to behave.

The night sky provides a graphic basis and exciting stories for learning about the good and the bad, to learn about right and wrong behaviour and to be encouraged to identify with any of several positive role models.

Because of the way the earth is tilted relative to our galaxy, there is a considerable part of the sky that we see the whole year round. This is the southern sky.

In contrast the northern sky shows us stars for only a few months at a time especially the ones closer to the horizon.

In the south we see Bunya the Ringtail Possum, the courageous brothers Berm, War the Crow and his wife, the pair of Brolgas, the Fairy Owl and the head of the giant Emu.

They move through the sky as if part of a gigantic wheel. If a star is noted at say 9pm then by 3 am, six hours later, it will have moved a quarter of the way around the wheel. It does a full cycle plus one degree every twenty-four hours.

This is why it is sometimes hard to pick the Southern Cross. Most of the time it is not upright in the position we recognise from the Australian or New Zealand flags. If we are looking for the Southern Cross in the early evening sky, the cross is upside down and very low down on the horizon, often obscured by trees, buildings or hills.

But continual observation of the movement of the Southern Cross helps us to understand the rotation of the southern sky. The line of symmetry also helps us find the centre of the great wheel.

There is no convenient star in the southern sky to act as a “pole” star as there is in the northern sky. Astronomers do refer to the South Celestial Pole, which is in the centre of the great circle but with no star visible to the naked eye.

Many of the Boorong celestial phenomena make their way from east to west across the northern sky. The higher they are in the northern sky the longer they are seen. For instance Kulkunbulla (in Orion) no sooner disappears at sunset in June when he reappears just before dawn in the north-east.

Purra, low down in the sky, not far above the horizon, appears and disappears in the space of a few months.

The closer their rising to the east, the higher they will appear in the sky and the longer is their sojourn in the night sky. We can compare Neilloan and Otchocut both of whom appear around March. Neilloan comes up in the north-east and Otchocut in the east.

With each succeeding night they move one degree to the west so that in March they appear about 5pm, byJune Lyra is in the north at 1am, having appeared at about 10pm.

When Neilloan no longerappears in October, Otchocut is still high in the sky and does not disappear until December.

The observer will note that when phenomena appear first in the northern sky they will be angled to the right. When they are leaving the sky in the west they are angled to the left.

This is that middle part of the sky we see when looking directly east then tilting the head back to look directly overhead, then having to turn the body around so as to continue the overhead gaze down to the western horizon.

This is the passage of Warepil the Wedge-tailed Eagle and of Unurgunite, the Jacky Lizard who travels not far behind. The illustrations of these two ancestral heroes are as seen in the western part of the central sky. If the observer is prone on the ground with to the west and face uppermost then these two figures are the right way up across the whole sky.

Warepil appears an hour or two before dawn in mid-winter in the eastern sky and is still in the western sky for an hour or two after sunset. In the summer months he is directly overhead at midnight.

Scorpius is a key European constellation to be found on the southern side of the central sky. The Red-rumped Parrot Djuit is based on Antares, the brightest star in Scorpius and two figures are found at the sting end of the scorpion’s tail. These are Karik Karik the Australian Kestrel and Karik meaning the spear thrower.

It is from Scorpius to the Southern Cross that we find the large dark patch, which becomes Tchingal the giant Emu, more readily seen if there is no moon and no cloud.

Djuit and Karik Karik are in the sky from April till December.

Won, the boomerang thrown by Totyangguil, otherwise known as Corona Australis, is further south than Scorpius and is out of the sky only between November and January.

These are the two brothers who were noted for their courage and destructiveness and who spear and kill Tchingal, the giant Emu that eats people.

Known elsewhere in Wergaia as the Brothers Bram they were ancestor heroes revered over a wide area. Based on the two pointers to the left of the Southern Cross, Alpha and Beta Centauri, the”gle” part of their name is probably a locational device meaning “up therein the sky, just to the left of the cross”.

Alpha Centauri is actually two individual yellow stars accompanied by a red dwarf about two degrees away.This one is a flare star, increasing its brightness by one magnitude for several minutes.

Nearby stars located with binoculars create the image of a human figure in the act of throwing a spear. The spear is aimed at the dark patch at the bottom left of the cross. This humped black shape is the fallen Emu transfixed by the spears of the Brothers Bram. The star at the foot of the cross is the point of the spear that has pierced Tchingal’s neck and that in the arm on the right has gone through the rump.

The other meaning of Berm Berm is the Red-kneed Dotterel or Sandpiper who lives on the edges of swamps.They are extremely active birds and are very alert to predators and intruders. They run with quick strides and frequently jab their bills like spears into the soft mud at the water’s edge. This kind of behaviour coincides with that of the heroic brothers.

There are several stories involving these ancestral figures who have slayed other people eaters and battled the elements in heroic circumstances. Their adventures are recorded in the fashioning of the landscape and they are remembered as protectors of the weak, as successful hunters and creators of country.

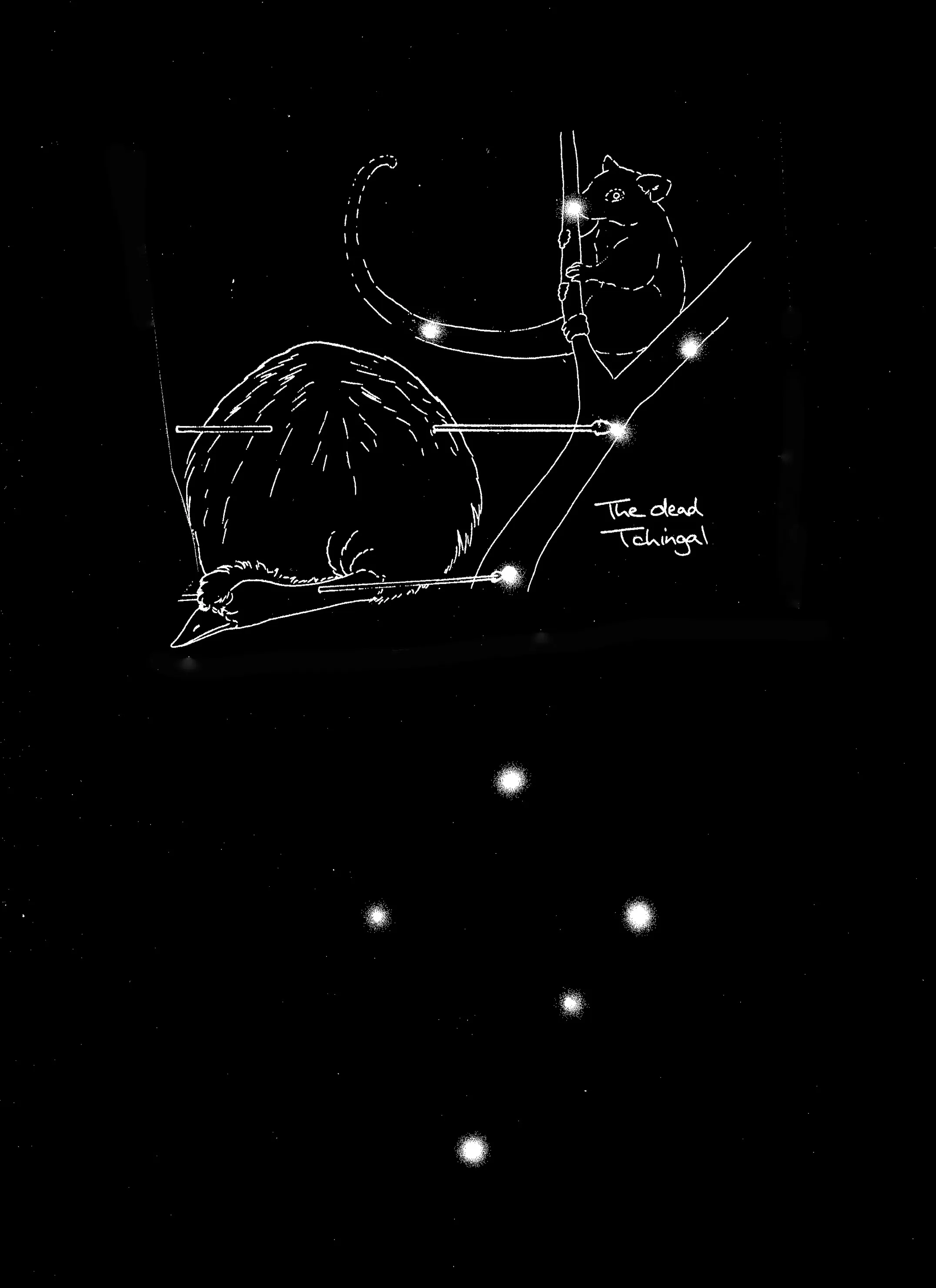

Bunya was pursued by Tchingal, the giant Emu who eats people. Bunya escapes by dropping his spears at the foot of the tree and runs up it for safety. For such a cowardly act he becomes a Possum forever destined to live in the treetops.

Bunya, pronounced “boonyah” as in “book” is the Ringtail Possum whose head coincides with the top star in the Southern Cross, Gamma Crux. The cross is the tree that Bunya runs up for safety.

His ear tips are apparent in the two little stars above and to the right of the top star. His back is to the right hand side and his tail is very evident below and in the centre of the cross, veering out to the left.

Because of atmospheric conditions and the way the brain can select stars to the exclusion of others, Bunya’s tail is not always exactly in the same place. Even in the one night his tail may be in more than one position.

The head of Tchingal is the dark patch at the lower left of the tree, known to European astronomers as the Coal Sack. The Possum’s head is tilted slightly so that he looks down towards the Emu’s head.

Possum skins kept the people warm in winter. Forty square cut skins, sewn together, provided a warm coat for an adult, worn inside out as protection against rain and doubled as a doona for sleeping.

Chargee means sister, so Chargee Gnowee is the sister of the sun. We know her as Venus, the planet that takes 225 days to revolve around the Sun and when seen in the dawn sky is known as the morning star, or in the evening sky is known as the evening star.

She is husband to Ginabongbearp who we know as Jupiter and like him is alone in the sky. She is seven times brighter.

He, with Warepil, is the other named chief of the Nurrumbunguttias and is the husband of Chargee Gnowee or Venus. He takes a similar path across the sky as his wife but takes nearly twelve years to orbit the sun.

Jupiter, the planet, does not appear as part of any constellation, is usually alone in the sky but its brightness is such that on a clear moonless night it can cast a faint shadow.It is similar to the stark whiteness of a Cockatoo against the dense green of the forest.

Ginabongbearp literally means“foot of day” in one translation and “pulling up daylight” in another. It is not unusual for the screech of the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo to be heard at sunrise in the backcountry.

Carrying or wearing white Cockatoo feathers is a sign of peace in parts of northwest Victoria when arriving at a stranger’s camp. This custom is still in use today.

Gnowee is the sun, an Emu egg prepared and cast into space by Pupperimbul before which the Earth was in darkness. The word has currency throughout the several languages and clans in north west Victoria.

Gnowee provides warmth and light, necessary for the growth of plants and the well being of animals. This generative characteristic means that the sun is recognised as female in many Aboriginal societies.

Djuit is the Red-rumped Parrot and the son of Marpeankurrk. This one is based on Antares, a red supergiant which is the chief star in the constellation Scorpius.

Antares also has a sixth magnitude blue companion. Coincidentally the Red-rumped Parrot has blue flight feathers, which are very obvious on the wing.

The other coincidence relates to the position in the sky and the breeding season. Djuit is virtually overhead in the August evening and disappears in the western sky by early December. The breeding season for the Red-rumped Parrot is from August to December.

We don’t know why Djuit is in the sky. He would have an important place in the song cycles as the son of Marpeankurrk but nothing is known. The red colour could be a reference to blood and therefore to circumcision or ritual scarring, but we do not know this as a fact.

We do note though that Stanbridge gives Boorong references for fifteen of the twenty brightest stars in the sky. There is no reference to the other five bright stars. It is possible that these five relate to information that was private, or secret or sacred, and therefore not to be passed on to a stranger. It may be that his informants were men and that these constellations related to women’s business.

Gellarlec (hard “g” andaccent on the first syllable) is the songman, based on Aldebaran, standingerect in the northern sky between Larnankurrk and Kulkunbulla.

Alderbaran is the left elbow of Gellarlec who hold the knowledge essence of the clan. Whether a song is for fun or for the maintenance of life knowledge or to celebrate the seasons or to remember a specific totem, or whether it is a single occasion or part of a song cycle, the songman remembers the words and the order in which the song is sung. The songman is a man whose integrity is unquestioned.

In Aboriginal society three main senses are used to reinforce learning throughout life. A Dreaming story will be sung (auditory sense), and danced (kinaesthetic sense) and its preparation will require body painting and the creation of ceremonial materials (visual sense). All senses are drawn upon. Each reinforces the other. This begins to explain why it was not necessary to have a written culture to ensure survival of knowledge and for successful living across a thousand generations.

The name Gellarlec derives from the Pink Cockatoo, also known as the Major Mitchell Cockatoo. This colour is consistent with Aldebaran which is a red giant of magnitude 0.9. The Cockatoo’s voice is distinctive, described as a quavering, falsetto, two note cry.

This may also equate with the songman’s voice.

Kourt-Chin refers to the Clouds of Magellan which are the male and female Brolga, the larger cloud being the male and the smaller cloud being the female.

Both are miniature galaxies, satellites of the Milky Way and rotating around the south central celestial pole on the side opposite to the Southern Cross. Each cloud resembles the colour and pitted shell of the Brolga egg. The size and shape may also resemble the island nest made in the swamp with the darker patches resembling the eggs.

These birds breed from October to April at which time the Magellanic Clouds are at their most prominent position in the sky. Famous for their dancing, Brolgas line up opposite each other, bowing and bobbing their heads as they advance and retire. These elaborate dances may also be part of the courtship display but also occur outside of the breeding season and help to maintain and strengthen pair bonds.

When the observer incorporates nearby stars then the two figures appear, the larger one trumpeting and the smaller one displaying, but dancing as a pair towards each other.

Along with the Eagle man and wife and the Crow man and wife the Brolgas form the third parenting model couple in the Boorong night sky.

Kulkunbulla is a number of young men dancing and probably two because “bulla” means two. “Kulkun” is the word for a young man or boy about the age of puberty. There may also be a connection with the kind of tree that grows in the Mallee; slender, dark and of great strength and resilience.

The Stanbridge reference is to the stars in the belt and scabbard of Orion.

We need to remember that Orion is seen from the reverse perspective in the northern hemisphere, which is why his scabbard is pointing upwards in the southern hemisphere.

Larnankurrk is a group of young women beating time for Kulkunbulla, the young men dancing. Based on the Pleiades, this star cluster represents to the Boorong the young women of the camp beating time on their rolled up Possum skin cloaks. Struck with great precision, and in unison, the drummer provided a solid percussive beat for the young men dancing.

“Lar” means stone, probably referring to the grinding stones habitually left at camping sites, thus “stone”becomes synonymous with camping place. The locality Lah on the Henty Highway, fifteen miles north of Warracknabeal, has a major stone quarry. “An” express direction from a place and ‘Kurrk” means blood or woman. It is often used as a suffix signifying female.

The Pleiades have a female reference in many parts of Australia. It is the brightest and most famous star cluster in the sky, it covers about one degree of space and is often referred to as the Seven Sisters because approximately seven stars are visible to the naked eye.

Marpeankurrk is the discoverer of the Bittur and the teacher of the Boorong when and where they were to find it. When she is in the north at the evening, the Bittur are coming into season. When she sets with the sun, the Bittur are gone and summer begins.

The Bittur is the larvae of the White Ant or Termite which are placed upon large sheets of bark and lightly roasted over the coals. Nutritionally superior to other animal foods they are an important source of protein during August and September when game is scarce.

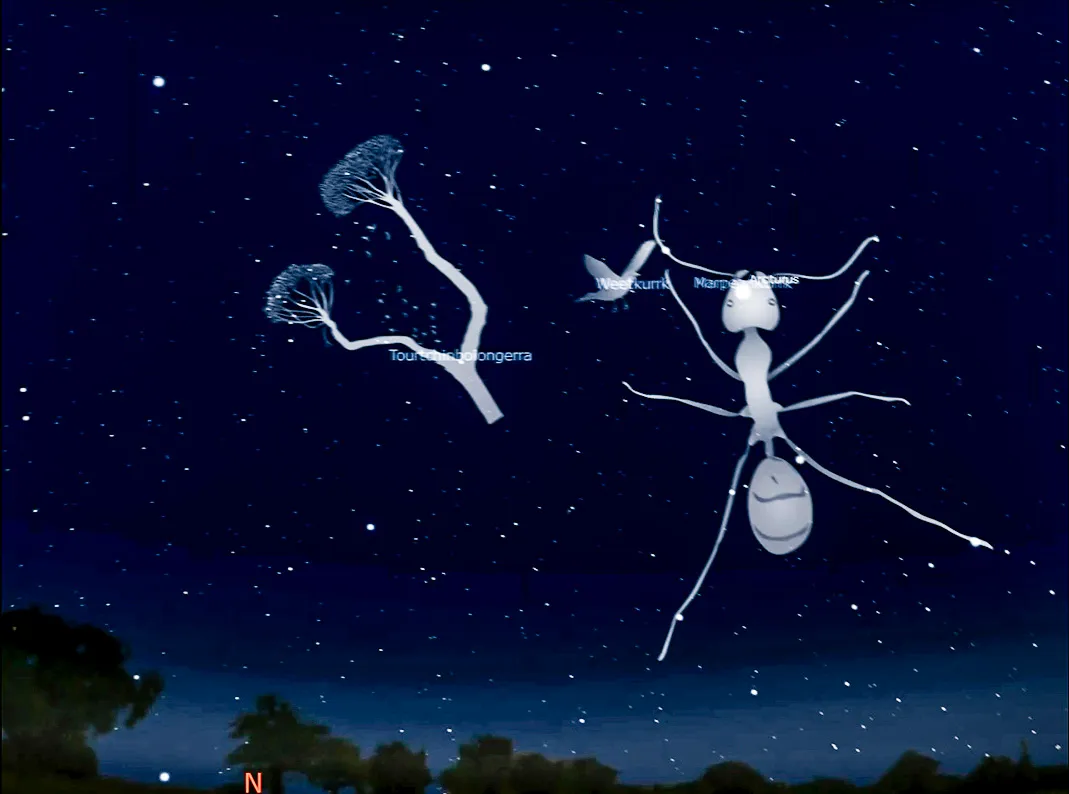

Thus the discoverer of the Bittur has the respect of the people and Marpeankurrk is a creator spirit teacher. She is based on Arcturus, the brightest star in the sky in the brightest of all the female Boorong constellations. Arcturus appears as the head of a giant ant or termite in the northern sky.

It is possible that the name is derived from “Mara” meaning meat-ant, “binj-binj” the Brown Tree-creeper and “kurrk” being the female suffix. The Brown Tree-creeper is fond of ants and breeds from June onwards, the time the Bittur are coming in to season. A family of Tree-creepers occupies a large territory in which they hunt for insects by pecking and probing into crevices and peeling bark.

The Brown tree-creeper is often seen in groups of three or more, all of whom help feed the young in the nest. This family therefore provides a useful model for cooperative food gathering.

A part of the galaxy is two Mindii enormous snakes, which made the Murray (Millee) according to the Stanbridge account. The dark section of the Milky Way just west of the Southern Cross has a definite S bend very like the bends of the might Murray and similar to that of a snake in motion.

Mindi is the huge snake that could wreak havoc (including disease) on the people in certain situations. Its earthly counterpart is the Carpet Python and the earliest known journal reference is from Robinson in 1843 who mentioned a policeman killing and skinning a male “Mindy” over six feet long.

Djadja Wurrung neighbours to the southeast of the Boorong said that the home of Mindi was Mount Buckrabunyule, near Charlton, in northwest Victoria.

These clans believe that the Mindi was the originating cause of the smallpox epidemics, which caused a huge number of deaths after its introduction by the British at Botany Bay. Ceremonies were held in awe of Mindi or to mime the destruction of Mindi. They may have had some relationship with the Rainbow Serpent ritual in other parts of Australia.

Mindi wound his tail around a tall tree then extended himself over the treetops for several miles.

He is in the night sky and can be seen in the illustration for Warring, to the right of the picture, as a dark patch.

Mityan is the moon, a male of sexual disrepute who lost a fight over another man’s wife and who has been wandering the heavens ever since.

Mityan’s earthly counterpart is the Quoll or native cat which used to inhabit parts of Victoria and New South Wales. Its white-spotted brown coat is clearly reminiscent of the various phases of the moon, from the slim crescent through to the full moon.

In contrast to the Eagle, Crow and Brolga, this species of Quoll, Dasyrus geoffroii, does not pair off for life, in fact their mating usually does not last beyond copulation. Subsequent copulation for both males and females is with other individuals they have not yet copulated with. Mating may last from three to seven hours.

The Boorong story has Mityan falling in love with one of Unurgunite’s wives, and while trying to induce her to run away with him, is discovered by Unurgunite. A fight takes place, Mityan is beaten, runs away and has been wandering ever since.

Mityan thereby provides a story of moral sanction of how to behave in a relationship between man and woman.

This species of Quoll had a blood thirsty reputation in the Murray scrubs, was solitary in its habits, strictly nocturnal and was the terror of the Sulphur-crested Cockatoo. If hungry it may attack any other animal of whatever size. The female eats her own children if food is scarce.

The unpleasant behaviour of the Quoll is an interesting contrast with the model couples who inhabit the Boorong night sky.

These are the original race who once inhabited Earth but who now live in the sky and possess special powers. Their earthly counterpart is the Black-faced or Mallee Kangaroo which is distinguished by an apron of light fur extending from the tip of the nose and under each cheek down to the chest. It is not unlike the long grey beard of the venerated elder of the clan.

“Nurrumbut” is the Wergia word for old man and the last part of the word is a species of Kangaroo, Probably the Black-faced Kangaroo. These old spirit people now inhabit the heavens and Warring, the Milky Way, is the smoke from their camp fires.

They still possess spiritual influences upon the earth and can create fearful atmospheric conditions if things displease them.

If Pupperimbul were to be killed there would be a fearful fall of rain. The Pupperimbul took the Emu egg into the sky to be the sun. Before this the Earth was in darkness.

All the stars as well as everything in space have emanated from the Nurrumbungattias.

The Australian Kestrel hovers in the night sky exactly mimicking the real bird in the day sky. It can hold its position for several minutes as it hangs suspended examining the ground for the movement of small creatures which are its prey.

The same name Karik is used for the spear thrower. This wooden instrument is used as the extension of the arm which allows a spear to be thrown harder, faster and with more accuracy. A hook at the end of the spear thrower fits into a hollow made at the end of the spear to prevent slippage when the spear is thrown.

Neilloan is the Malleefowl creator being in the northern sky who appears in March and disappears in late October. Her appearance coincides with the time that the Mallee Fowl begin to make their incubation mounds. Her disappearance coincides with the beginning of egg laying.

The Boorong word ‘loan’ or‘ lowan’ is still commonly used and the constellation actually looks like this bird in profile.

The large star coinciding with the foot of the bird is the fifth brightest star in the sky, known as Vegaor Alpha Lyrae. It is the powerful kicking motion of the bird that enables it to construct the huge mound in which the eggs are deposited to hatch them out from the warmth of the mound.

A famous Nebula called the Ring Nebula, elliptical in shape and currently beyond the reach of human eyesight is part of this constellation. Over the last 20,000 years it is possible that it may have been visible as an egg shape, highly significant for an egg-laying creator being.

Another extraordinary coincidence is the meteor showers, which radiate out of Neilloan in April, June and July. They remind us of the dirt, twigs, leaves, bark and other material flying through the air as the Malleefowl kicks material away from or onto the mound.

The Malleefowl is a generous layer of eggs, as many as thirty during a laying season from September to March. Each is the equivalent volume of four hen eggs, rich in flavour and highly nutritious.

Malleefowl mate for life and exhibit strongly defined gender roles. The focus of their activity is the production of the next generation and there is great co-operation in mound building, egg-laying, food gathering and in the defence of the mound against predators.

Boorong parent and child observing the Malleefowl would note all kinds of detail about the female role, the male role and the team work, the specialisation and the tenacity required during the whole breeding period. Observation of Neilloan in the sky is a constant reminder of what is observed on the ground.

With each successive visit to the Malleefowl country a youngster would absorb more and more about the lifecycle and the behaviour of Mallee Fowl.

Thus in leading people to this wonderful food source the ancestral creator being also leads them to a model couple in a parenting role.

Maybe this great fish was part of the lake system thirty thousand years ago, prior to the dryer climate change that has occurred since. Maybe a sifting of ancient beach sands, still to be seen in the dune ten metres above the present shore line would reveal the gill bones of the Murray Cod.

Anyway, for the last few thousand years the lake has been too shallow and its filling too infrequent to be regarded as a home for the great cod.

None the less the Boorong had direct contact with the giant fish in its major habitat they called Mille and which we now call the Murray. They used to meet with the Dadi Dadi clans at Kulkyne, the Latji Latji at Euston and the Watti Watti at Nyah at regular intervals to trade, to arrange marriages, for celebrations and for ceremonies.

The Murray Cod is the largest fresh water fish in Australia and spawns in the late spring and early summer when the water temperature is just right. Visits to the great river were likely to have occurred when Otchocut left the sky, at about this time. Some of the colours of the stars in Otchocut are white, gold and yellow-white which coincide with the colours of the cod.

In the northern hemisphere the constellation is known as Delphinus, the dolphin. The word Otchocut may be derived from the word ’tyaka’ to eat. The prefix O may be an expression of delight with this food item, thus Otchocut may mean good tucker.

This tiny creature has the honour of taking the Emu’s egg into the sky to become the sun, before which the earth was in darkness.

There are two birds that fit the description ‘the little bird with the red patch above the tail’. One is the Shy Hylacola, the other is the Diamond Firetail. Each bird has a distinguishing red patch above the tail, the Hylacola’s being described as a rich chestnut and the Firetail as crimson. Both live in northwest Victoria.

A distinguishing feature of the Shy Hylacola is its spring song which is said to be persistent and is often heard just before the dawn. A distinguishing feature of the Diamond Firetail is for the male to carry a long grass stem to the top-most branches of a dead tree to begin his courtship ritual.

Is it the Shy Hylacola, also known as the Red-rumped Ground Wren whose singing up the sun has given rise to Pupperimbul or is it the carrying routine of the Diamond Firetail?

Whichever it is, if Pupperimbul is killed, vengeance would follow as a deluge of rain, one of the forces of nature unleashed by the Nurrumbunguttias, who count Pupperimbul as one of their material forms on earth.

There is no constellation or star indicated for Pupperimbul.

Purra is the Red Kangaroo who is pursued and killed by two hunters, Yurree and Wanjel.

Purra appears in the northeast sky just before dawn in mid to late August and disappears in the early evening in late February, followed later by her pursuers. A line drawn from Wanjel through Yurree towards the horizon connects with Purra.

The earth’s atmosphere affects the clarity of celestial objects close top the horizon which makes sighting Purra difficult. It is rather similar to sighting a plains kangaroo at a great distance in the summer heat through a mirage.

Whilst it prefers the open plains habitat, it seeks the shade of scattered trees and at the height of summer when temporary waterholes and creeks have dried up it has to make for permanent water to drink. It is here that the hunters lie in wait to strike down their quarry.

The major star in Purra is Capella or Alpha Aurigae, a binary consisting of two yellow stars, the colour being not too distant from the pater subspecies of Macropus rufus. Nearby stars help create the impression of the kangaroo leaping at full speed to the east very like the roadside warning sign or the reverse of the last Australian penny coin.

One kangaroo provides bulk meat, which may last a family for several days. Careful preparation includes burying the bile duct, grilling the entrails, singeing the fur, sewing the incision to preserve the liquid and cooking underground. The initial cooking produces rare rather than medium or well-done meat and the left overs from the first feasting are subsequently grilled in the coals the next day and the day after. Any contamination is thereby burned off. Due care means that refrigeration is not essential for healthy living in remote desert areas.

The presence of Tchingal in the night sky is a constant reminder of the forces of good and evil and the ultimate triumph of the ordinary man, with some help from the protector ancestors.

Tchingal is the giant emu that eats people and therefore made families live in constant fear of their lives.The crow grew tired of the constant harassment and told of his dread to the brothers Berm. They promised to help him if crow would lead them to the fearsome giant.

The ensuing battle raged over a wide region, which helped to define the current landscape and ultimately their quarry was cornered. To their surprise it was the Singing Bushlark, Weetgurrk, that delivered the death blow, the final spear thrust, which secured the future safety for all people.

The heroic brothers then split each feather of the giant emu down the middle, casting one half of the feathers on the right hand side and the other half on the left, making two heaps. One of these heaps became the cock, the other the hen of the present race of emus, which are much, much smaller in size.

It was arranged that all future emus should lay a number of eggs instead of one only as the giant had.The splitting of the feathers is still easily observable in the twin-shafted feathers of all emus today.

On first sighting Tchingal in the night sky the observer is overwhelmed by its immensity. Its head is what other astronomers call the Coal Sack, just to the bottom left of the Southern Cross, its neck extends down through the pointers and its body is the large dark patch just before reaching Scorpius. Its legs hang down into the tail of Scorpius.

Once it is killed the body crumbles into a heap at the foot of the tree up which Bunya has sought refuge, with one spear through the rump and one spear through the neck.

The word Tchingal is probably a nickname for the departed giant emu, literally meaning ‘long bones’ or‘lanky’.

The darker Emu, the female, belongs to the Gamaty moiety the Red-tailed Black Cockatoo. The grey Emu, the male, is the opposite moiety, Gurogity, represented by the Little Corella.

Totyarguil is a creator hero living in the northern sky whose physical exploits include the making of Mille, the mighty River Murray.

Totyarguil is noted for his courage, tenacity and physical endurance in pursuit of the giant fish. As this great cod tried to elude his spears it tore through the bank of the waterhole, carving a deep channel until brought to rest by a final spear from Totyarguil somewhere far in the west.

Otchocut, the giant fish of the Boorong pantheon is in the sky just to the east of Totyarguil. Neilloan, mother to Totyarguil, is on his other side but lower down in the sky.

His name is derived from the word for star ‘tot’ or ‘tourt’ and the name for the Purple Crowned Lorikeet. The constellation Aquila on which Totyarguil is based has a number of stars which reflect the coloration of this bird; yellow, white, blue and purple. A neighbouring group to the north, the Madi Madi people, use a similar word to denote the rainbow.

Another coincidence is that this constellation is at its highest point in the northern sky at evening in late August, which is the beginning of the breeding season for the Purple Crowned Lorikeet. The season lasts until the end of December, which is when Totyarguil leaves the sky.

In his absence, the mother of his wives Yerredetkurrk has gained maximum visibility in the southern sky. Through their physical relationship in the night sky we learn about a fundamental marriage law for all of Aboriginal Australia, the law of mother-in-law or son-in-law avoidance.

As Yerredetkurrk continues her circular path around the south celestial pole and moving down to the horizon so Totyarguil climbs higher and higher to his maximum visibility in the evening sky.

Such oppositional movement provides a dynamic and visual representation of the laws of avoidance, a law, which regulates behaviour in support of proper marriage, an absolute necessity in maintaining genetic hygiene in small population pools.

If a forked tree is split slightly by a windstorm when the tree is growing the wood around the split decays and rots and a cavity forms in the bole of the tree. When it rains, water runs down the branches into the hollow until it fills. Such water can remain there for a long time being replenished by every shower.

Water filled trees may contain a complex community of insects whose life cycle requires small reservoirs for breeding purposes. Thus birds will be attracted to the insects, and in very dry country will seek out the tree as a source of water as well as food.

Thus the ‘V’ shape of an upside down Coma Berenices provides the fork of a tree, probably the Needlewood Hakea. The faint stars within the fork are the small birds, probably Willie Wagtails. Each of these birds had its own name but these were forgotten by the time the Boorong people told William Stanbridge about this configuration.

The merit of this northern sky constellation is realised from the dry riverless country occupied by the Boorong clan. Women who were out gathering food or men out hunting would note such a tree from a considerable distance and recognise its thirst quenching potential.

“Tourt” is star. ‘Chin” is the Needlewood Hakea. ‘Boren’ is water. ‘Gerra’ is close to the word for Willie Wagtail.

Tourtchinboiongerra is a wonderful constellation for instruction to youngsters. It looks exactly like what it is meant to represent and its story is unforgettable.

William Stanbridge notes that the Boorong people pride themselves on knowing more of astronomy than any other tribe. David Mowaljarli says of his own people in his own country, the Kimberley, that everything is represented on the ground and in the stars, that everything has two witnesses, one on earth and one in the sky.

Lake Tyrrell has the extraordinary capacity to demonstrate the unity between sky and land. On a still, clear, moonless night with a little water in the lake, it acts like a gigantic mirror reflecting all the stars in the night sky. Being a little way out in the water is like being suspended in space with stars around, above in the sky and below as reflections in the lake.

We therefore understand better why ‘tyrille’ in Boorong language means ‘space’ or ‘sky’.

Even tiny people can be brave and protecting of their families. Unurgunite is the Jacky Lizard who fights off Mityan the moon’s effort to seduce his wife.

Unurgunite’s tail is unmistakable and is the most useful guide to his appearance in the Boorong night sky. He is to be found a little to the east of Warepil in Canis Major. The European custom is to give each star in a constellation a letter of the Greek alphabet corresponding to the descending order of magnitude (or brightness) and since Unurgunite is Canis Major Sigma it means that he is the eighteenth in order of brightness in that constellation.

The Jacky Lizard is sometimes referred to as the ‘bloodsucker’ lizard which relates to its behaviour when cornered. It turns its face to its pursuer with mouth wide open in a threatening manner.

Unurgunite’s heroic efforts in beating Mityan in a fight, in protecting his wife against this promiscuous reprobate, have earned him an honoured place in the celestial panoply.

Wanjel is the Long-necked Tortoise, based on Pollux, in Gemini, in the northern sky. Pollux, a giant star with magnitude 1.1 is described as an orange star. Coincidentally, the Long-necked Tortoise has an under shell marked with orange-red patches when very young. The orange colouration bleaches with age.

The Tortoise has a long snake-like neck and if roughly handled exudes a clinging foul-smelling liquid.It is known sometimes as the stinking tortoise. The female lays eight to twenty-four eggs and juveniles appear from January to March. Early evening in March is when Wanjel is at its most visible position in the northern sky.

They make good eating and are generally taken when the water in the billabongs and creeks is low at the height of summer. This is after the time the juveniles have appeared.

Of all species kept in captivity, this is the one said to be the easiest to maintain. If provided with satisfactory surroundings it will readily breed in captivity. It is often seen in pet shop aquarium tanks.

Wanjel and Yurree are the hunters who pursue Purra the Red Kangaroo.

War, pronounced Wah, is the male Crow, the brother of Warepil, and the first to bring down fire from space (Tyrille) and give it to the Aborigines, before which they were without fire.

War is based on Canopus, the second brightest after Sirius (Warepil). A straight line from Warepil through Canopus to the horizon gives the direction south.

War is a yellow-white supergiant of magnitude 0.72 and is seen in the sky the whole year round but may be hidden behind the trees from July to September. These are the months that the crows lay their eggs.

It is the Crow who told the brothers Berm about the giant man-eating Emu Tchingal and where to find him. He also helped to carry their weapons and to make a positive identification of this enemy of the people. The Crow’s useful service to mankind is recognised by the fact that the grow totem grouping ‘wangaguliak’ includes man, ‘guli’ is the word for man.

In September War looks likethe illustration with wings below the body. In March the reverse happens asillustrated with the wings above the body.

As mature Crows pair off they occupy a suitable piece of country in which they find most of their food, and roost and breed. They mate for life and occupy their territory all year round, reinforcing their boundaries each morning by patrolling and making the countryside echo with the characteristic ‘wah’ sounds.

Pairing for life, remaining monogamous, having children and rearing them are significant elements shared with the people whose totem included the Crow.

That these elements are also typical of the eagle, who, together with the Crow, are the two brightest stars in the sky, suggests that the Boorong people placed important emphasis on these two night sky heroes.

War, pronounced ‘Wah’, is the word for Crow. It is the sound that the Crow makes as it flies around its territory. ‘Collowgulloric’ may be derived from words which mean ‘to go with’. She is the wife of War.

When the Boorong people were informing William Stanbridge about the night sky, the major star in the constellation, Eta Carinae, was of the magnitude – which is extremely bright. Her husband’s star Canopus is currently of magnitude 0.72. Thus her presence in the southern sky at this time would have been quite spectacular.

Crows do not breed until they are three years old or older and until then they forage in open spaces from place to place in flocks of thirty or more.

Only when they pass through vacant territory is there an opportunity for a pair from the flock to mate and take over that territory. They pair off for life and rear their children until they are old enough to join a passing flock.

Warepil, the Wedge-tailed Eagle, is Australia’s biggest bird. Appropriately it is based on Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. Warepil’s flight is directly overhead in summer and autumn from east to west. He is pictured here as west of overhead.

After their early morning quartering at tree-top level a pair of Wedge-tailed Eagles may spend part of the day circling and gliding at heights of up to two thousand metres. The eagle seen overhead like a pinprick in the sky in the middle of a February day is still there at nightfall, only now it is Warepil, slowly making his way across the sky.

Warepil is brother to War, of the same moiety, but this is from a different sub-group. Both these subgroups share the same ancestral home or watering place. Warepil is a chief of the Nurrumbunguttias which places him as the most senior man in the celestial hierarchy.

Warepil’s wife is nearby and their presence in the night sky mimics their earthly behaviour. Sometimes seen alone, they are usually observed in pairs, gliding or soaring over the country or perched silently on dead or sparsely foliaged trees. Their display flights are spectacular examples of aerobatics, flying steeply upwards, plummeting down with closed wings flying into then away from each other, sometimes appearing to clutch each other’s talons and sprawling downwards, only to breakaway again.

Not only do they play together but they hunt co-operatively and both sexes share in incubating the eggs and feeding the chicks. They make an excellent role model for parenting.

This one is the female eagle and the wife of Warepil. She is based on Rigel, the brightest star in Orion. Other stars nearby, picked up through binoculars, reveal her to be flying through the night sky, not so far from her husband Warepil in Canis Major.

Similar in size and plumage to the male, the female Wedge-tailed Eagle shares the territorial exploration of their habitat at the hours of sunrise and sunset. For the rest of the day she may be seen soaring high above not too far from her partner, or at rest near the nest.

For proper marriage Collowgulloric Warepil has to come from the opposite moiety to Warepil. Their children will take their moiety identification from their mother, according to local custom.

Use a planisphere to find where the larger well known stars are in the night sky. The reader may need to use binoculars to find the smaller stars.

A star and planet reference book is handy but you will need to check where the book has been published. If printed in the northern hemisphere then many of the constellations will be in the reverse of the way we see them.

This is probably the white hazy part of the Milky Way that represents the smoke of fires of the Nurrumbunguttias. It was known as Warring, the Galaxy, of which the Earth’s sun is one of at least 100,000 million stars.

In flat desert country peopled by the Boorong, smoke can be seen for great distances and they could read in the smoke much intelligence, for example as to whether it came from cooking, for hunting or was made for deliberate communication.

David Mowaljarli says:

"As you sleep beside the campfire at night you may think you’re stiff and turn over, in reality, you are following the Milky Way as it turns around the Earth. Everything is represented in the ground and in the sky… all is one and we’re in it. As you see the Milky Way it ties up the land like a belt, right across".

Weetkurrk is the daughter of Marpeankurrk and lies to the west of Arcturus.

On the ground she is the Singing Bushlark whose colouring ranges in the brown, buff or rufous and is believed to adapt her colour according to the local soil.

She sings aloft at considerable heights, often mimicking other species. Her own song is a tinkling sound.

Weetkurrk joined Berm-Berm-Gle, the brothers Bram, in disposing of Tchingal, the giant person-eating emu. When the lark saw them coming she came out, carrying a bough in front of her to hide herself from observation. When Tchingal was within range she cast a spear, which struck Tchingal in the chest and killed him.

The men were annoyed at this last minute intervention by the lark, which deprived them of the honour of slaying the enemy that they had pursued for so long. None the less, as a common enemy had fallen they did not quarrel about it.

Thus we learn how to successfully hunt the emu, the essentials of teamwork and the need to have restraints on personal pride when working towards the common good.

Won is the boomerang thrown by Totyarguil. This is most likely Corona Australis which is halfway between Totyarguil and the head of Tchingal.

There is another corona in the night sky, Corona Borealis. This corona is out of the sky before Totyarguil is most prominent. In contrast the southern corona is in the sky for the whole time that Totyarguil is present.

Each of these coronas are curves of stars that can easily be seen to represent a boomerang. One of the chief uses of the boomerang was in catching ducks in large billabongs parallel to the Murray River. A large net would extend from one side to the other at the narrow end of the lagoon. A number of men would drive the ducks towards the net, keeping them flying low by sending their boomerangs whizzing over the heads of birds, who thinking it was their enemy the hawk swooping at them, would keep flying low and crash straight into the net.

William Stanbridge did not state which corona was identified by the Boorong as Won. It is assumed to be Corona Australis.

The Owlet Nightjar or Fairy Owl has a special place in the lives of women in the south-eastern part of Australia. Its place in the sky is across the south celestial pole from the bottom star in the Southern Cross. A line dropped to the horizon from the midpoint between these two stars will give an approximate south.

Yerredetkurrk’s appearance in the night sky mimics her life on earth. Of all the nocturnal birds in Australia the Fairy Owl is the most widespread but one of the least often seen. Similarly Achernar, the star on which Yerredetkurrk is based, is often out of direct view, hiding behind the tree tops.

Its colour is blue-white, not unlike the soft grey plumage that makes up much of the birds feathers. The accompanying stars make it look very like a bird in flight carrying its prey inits claws underneath.

The Fairy Owl roosts inside hollow trees during the day and when nesting will sit tight and not be frightened into leaving its eggs or abandoning its young. Its flight is silent but erratic, more like a butterfly. The first four letters ‘yerr’ are a similar sound to the noise it makes during the first few hours after sunset.

Given its characteristics and qualities it is no wonder this bird has a special place in the lives of the women and why it is represented in the Boorong night sky as the Nalwinkurrk, the mother of Totyarguil’s wives. Hence a reference has to be made to the law regarding mother-in-law / son-in-law relationships.

The law provides the basis for establishing proper marriage and for preventing a potentially incestuous relationship. It is a genealogical necessity in small communities and the success of its implementation may be seen in the genetically healthy Aboriginal communities who have lived a 1,000 generations, like the Boorong.

Yurree and Wanjel are two young men who pursue Purra the Red Kangaroo and kill him and eat him at the commencement of ‘ the great heat’, that is, midsummer.

Yurree appears to be an abbreviation of yurin-yurin-njani, which is the Wergaia name for the Storm Bird or Fantail Cuckoo. Like other cuckoos, the Fantail lays its eggs in the nests of other birds, usually in the dome shaped nest of the Thornbill. It breeds from August to December.

It is mid to late August when Yurree is first sighted in the north-eastern sky. Based on Castor, one of the twins in Gemini Yurree is directly north in the evening during March.

The throat and breast of the Fantailed Cuckoo is a dull rufous quality. The multiple star Castor includes a red dwarf companion. Another coincidence relates to the time of arrival of the cuckoo in its yearly migration from the northern parts of Australia. This corresponds with the appearance of Yurree in the night sky.

I started out in 1993, found most of the creatures and the people within two years but took until last year to find Kulkunbulla. One of the Brothers Berm still eludes me.

Andrea and I met John and Kirsty Morieson in 2014 through an introduction by Niagara Galleries director Bill Nuttall.

We publish this web version of Stars over Tyrrell: The night sky legacy of the Boorong to honour John for his detailed and long term investigations of the Boorong night sky and for his deep understanding of why the Boorong must be remembered in the stars and night sky that so shaped the lives of Victoria’s Aboriginal people.

We would like to thank the astronomer and photographer, Alex Cherney, for his superb photos and time lapse movies of the Boorong night sky.

Thank you to Rob McLean for his photo of Western Grey Kangaroos.

We are grateful for the interest and encouragement shown by Doug Nicholls and Alan Burns, Bruce Baxterat Swan Hill primary school, Rodney Carter the chairperson of Swan Hill and District Aboriginal Cooperative, Boondy Walsh the Koorie Programs Convenor and students in Koorie Art and Design at Swan Hill TAFE.

We are grateful also to citizens of Sea Lake who have shown an interest in this research and subsequent projects, especially to Kate Atkin, Rob Frankland, John Horan, Wendy Hersey and Keva Lloyd.

A very special thank you to Kirsty Morieson for her assistance and friendship.

William Stanbridge 1857 On the astronomy and mythology of the Aborigines of Victoria, Proceedings of the Philosophical Institute, Melbourne

David Mowarjali and Jutta Malnic Yorro Yorro, Magabala Books 1993

Luise Hercus 1969 The language of Victoria: a late survey ANU

Luise Hercus 1992 Wemba Wemba Dictionary AIATSIS

R H Mathews 1904 Ethnological notes on the Aboriginal Tribes of New South Wales and Victoria, Part one, Royal Society of New South Wales

Ian Ridpath and Wil Tirion 1988 Collins Guide to Stars and Planets Collins

John Morieson 1996 The night sky of the Boorong, MA thesis, University of Melbourne

Mallee Fowl image - Russotwins/ Alamy stock photo